We were already in a housing crisis when COVID exposed and increased the vulnerability of those without access to affordable housing, the dangers of under-housing, and the cruelty of homelessness. Disgracefully, it is people on the margins and intersections of society who are most negatively affected, including racially marginalized and Indigenous residents, newcomers, and women.

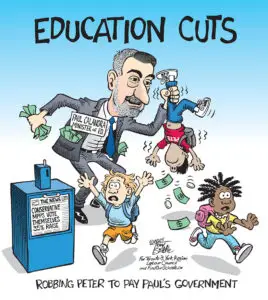

Our rental housing crisis is neither random nor typical of the situation in other developed countries. Instead, it is due to deliberate policy choices – and neglect – by different levels of Canadian governments, egged on by large private sector landlords and investors. The way out of this mess is to hold governments accountable and insist that they act on behalf of Canadians, not big business.

Who is Affected

Today we hear stories of union retirees receiving eviction notices from their landlords on phony grounds such as “cluttered balconies,” workers couch-surfing because they fell behind on rent and succumbed to the speedy eviction process, and far too many people getting hit with way- above-the-guideline rent increases. We also hear stressful stories from our union members who provide housing services, work with people who are homeless, provide legal services to those at risk of eviction, or who are housing activists outside of work.

There are over 100,000 households lingering on the waiting list for social housing in Toronto (TCHC owns approximately 60,000 units, and wait times of over ten years are common). Countless other families who are not on any list live underhoused or overextended financially, paying rents they can’t afford. There are nearly 10,000 homeless people in Toronto, and over 1,000 people in York Region documented as homeless or about to be.

The average rent for a two-bedroom apartment in the GTA is $1,591, and much higher in downtown Toronto. More than one in five renters spends over half their income on rent. However, the above rates don’t tell the full story since they reflect the rents currently being paid. If someone needs to find a home now, the entry rent for housing is much higher. With vacancy rates of less than 2%, any lower-priced units go quickly.

Supply of Affordable Housing

The supply of affordable housing is key. Developers have been powerful players in municipal and provincial politics for decades. They responded to rent controls by shifting most new building to condominiums, shrinking the rental market. Massive profits have come from urban sprawl and subdivisions that gobble up prime farmland. As the downtown core becomes redeveloped with luxury condos, the rapid entry of short-term rentals through AirBNB has taken thousands of units out of the housing stock.

The creation of new social housing has been limited over the past 40 years. For a few decades before that, building social housing, was supported by all levels of government. Visionary planning, such as that along Toronto’s Esplanade, introduced a new approach to housing in Toronto. While the St. Lawrence neighbourhood also contains market housing, the area has become a sustainable, mixed-use, mixed income community.

From the 1970’s on, Canada and Ontario supported an impressive building program of non- profits, co ops and publicly owned housing that funded more than 600,000 good quality, affordable homes across the country. The Labour Council Development Foundation became one of the key builders of co-ops in Toronto until the federal Liberals and then the Harris Conservative attacks wiped out these efforts.

Today hardly any public housing units are being built. Housing expert David Hulchanski says: “Canada has the most private-sector-dominated, market-based housing system of any Western nation … and the smallest social housing sector of any Western nation (except the United States).”

Why Housing is So Unaffordable

Greater Toronto real estate is a source of massive profit. With land and buildings being subject to the speculative local – and now global – market, every time the property is sold, the landlord charges more rent to recoup their return in investment. Since the 2008 financial crisis Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) have been buying up huge swaths of apartment buildings, promising big dividends for investors. One REIT bought 44 high rise apartment buildings (6,271 rental units) in the GTA in late 2019 for $1.7 billion. This trend towards concentration of ownership is accelerating and putting huge pressure on affordability.

What We Learned During Covid

We have seen and learned things during COVID: we have housed homeless people in hotels, giving people access to a place of their own to sleep and bathe and we have seen how unhealthy it is for people to be crowded into inadequate housing. Despite homelessness exploding during the pandemic, the Ford government ended its emergency ban on residential evictions in July, and pushed Bill 184 through the legislature. This strips away protections for tenants who are unable to pay their rent and makes it possible for landlords to obtain eviction notices without a hearing at the Landlord and Tenant Board. In August, the Ministry of the Attorney General ordered provincial Sheriff’s Officers to resume enforcing eviction notices.

To solve homelessness, we know poverty is one cause, and intersectionality makes it worse. But people who are poor can live well if housing is affordable. So the key issue is improving affordability (and providing high quality social services to help keep people in stable housing.) With shelters, our goal is to get rid of them through a progressive housing program, but until then we have learned from the pandemic that we can treat homeless people better.

The Government of Canada, through CMHC, has launched the Rapid Housing Initiative (RHI). It is a $1 billion program to help address urgent housing needs of vulnerable Canadians, especially in the context of COVID-19, through the rapid construction of affordable housing. This is a good start, but a late one, and must be sustained and broadened.

Ending the Housing Crisis

At its core, to solve the housing crisis, we need to move away from for-profit, market-based rental housing, and towards provision of much more social housing through co-ops, government-owned public housing, and non-profit organizations. In the meantime, we need strong rules to protect tenants and require affordable housing to be included in new developments.

On November 5 2020, the Labour Council resolves to:

- Call for the right to shelter and a fully-funded national housing program

- Demand that the municipal, provincial and federal governments immediately implement a comprehensive plan to fund and build permanent affordable social housing, including co-ops, government and non-profit organizations.

- Demand that the government of Ontario repeal Bill 184, reinstate and extend the ban on evictions and foreclosures, place all units, including vacant ones, under rent control to eliminate the two-tier system, ban “renovictions”, and implement a rent relief program

- Demand that the government reverse policy on vacancy decontrol, which incentivizes landlords to kick out tenants and hike up rent prices.

- Retain and expand affordable housing by implementing mandatory inclusionary zoning, regulating AirBNB, imposing a tax on vacant units, and enhancing RentSafe enforcement to ensure healthy homes

- Expand and humanize existing system of shelters and invest in Streets to Homes programs across greater Toronto

- Ask our affiliates to support our community partners, allies and union members who are working on tenant, housing and homelessness issues.